The Royal Guernsey Light Infantry - WW1

The 1914 – 18 war and the death of a regiment

In 1914, as Europe went to war, the Royal Guernsey Militia,

which at that time consisted of two infantry regiments

and an artillery regiment, was mobilised to replace

the regular army garrison which was withdrawn to reinforce

the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders.

Recruiting for The 16th Irish Division

St. Peter Port Gsy. 1915

Militiamen could not be sent overseas but the States

of Guernsey decided to offer a contingent of trained

men to the British Government. This offer was taken

up gratefully and in the end two full strength infantry

companies and a machine gun section were sent to join

the 16th Irish Division which was forming in Ireland

as part of Kitchener’s all volunteer army. The

companies were attached to 6 Royal Irish Regiment and

7 Royal Irish Fusiliers; the machine gun company went

to 6 RIR.

In addition a Divisional Ammunition Column was formed

from the Royal Guernsey Artillery and sent to 9th Scottish

Division. The 16th Division took part in the fighting

on the Somme in 1916 and the Guernsey Companies suffered

heavy casualties.

They were eventually disbanded in early 1918. In the

meantime the States decided that they would send a full

infantry battalion to the British army, probably because

they felt that the island should be seen to be doing

its bit.

As a result at the end of 1916 the Militia was suspended

for the duration of the war, conscription was introduced

and the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry was raised as

part of

the British army.

Most of the initial officers and men were former members

of the Militia but later drafts were not.

Before they left the Island a big parade was held

on L’Ancresse Common when medals were presented

to soldiers who had served with the volunteer companies

but were now with the RGLI after convalescing from wounds

received in action. They also received a set of camp

colours sewn by ladies of Guernsey.

After completing its basic training in Guernsey the

battalion left the Island for England on 1st June 1917

for advanced training at Bourne Park camp near Canterbury.

After advanced infantry training the battalion sailed

for France on 26th September.

On their arrival they were attached to 29th Infantry

Division which was commanded by a Guernseyman, Major-General

Beauvoir de Lisle and posted to 86th Brigade.

The Division was made up of regular army battalions

and had recently served with considerable distinction

in Gallipoli. However by the time the RGLI joined many

of the old regular soldiers had become casualties and

it is likely that the morale and motivation of the Guernsey

troops was higher than that of the battalions around

them. By the time the RGLI arrived in France to join

29th Division the Western Front had been in place for

some time.

.

A continuous line of trenches ran 475 miles from the

North Sea to Switzerland. A trench, in theory at least,

was a ditch some 10 to 12 feet in depth with a raised

fire step along the side facing the enemy. The sides

would be revetted with timber to hold back the earth

and there might be duckboards to keep the soldiers’

feet out of the mud - if they were lucky. Dug outs were

cut back from the side of the trench in which off duty

men could shelter and perhaps sleep. The trenches zigzagged

to prevent the blast from an explosion travelling along

them.

There were usually three lines of trenches - the main

or front line, the support and further back the reserve

lines. Soldiers would be rotated through these systems

so that in theory at any rate they could get some rest

while in support or reserve although much time in reserve

would be spent repairing trenches or carrying supplies

into the line.

After three years of continuous fighting the trenches were pestilential places where

the dead of both sides lay unburied and rats and vermin

flourished. Many areas were flooded

fighting the trenches were pestilential places where

the dead of both sides lay unburied and rats and vermin

flourished. Many areas were flooded

and men could and did drown in mud filled shell holes.

An incautious move could draw the attention of a sniper

and even if things were quiet there was a constant stream

of casualties from artillery and mortar fire as well

as from

sickness and disease.

The original idea behind the Battle of Cambrai was a

kind of large scale tank raid on the German rear areas

with the idea of destroying enemy personnel, guns, supplies

and most of all morale, but not to capture or hold ground.

The tank was in its infancy and nobody was

quite sure how best to use it and what effect it would

have on the enemy.

In the end the plan was much expanded into a major operation

with the objective of pushing the Germans back a considerable

distance. The attack was successful beyond the planners’

wildest dreams and almost all the objectives were achieved

with minimal - by Western Front standard - casualties.

The RGLI, for instance, took their objective, far behind

the German front line with only one officer and two

soldiers killed and 25 wounded.

But retribution was not far away. German doctrine set,

and indeed still sets, great store by early counter

attack on lost positions and ten days after the British

attack the Germans struck back. The Guernseys were ordered

to hold a little village called Les Rues Vertes on the

outskirts of Masnieres on the River Escaut and hold

it they did. Twice they were pushed out of the ruins

by weight of numbers, twice they retook the village

at the point of the bayonet, fighting with great tenacity

which aroused the admiration of all who watched them.

Sadly however such valour does not come cheap and by

the end of the fighting 40% of the battalion’s

total strength of 1311 all ranks were dead, missing

or wounded.

It was the end of a generation in Guernsey and the

Island watched, numbed almost into disbelief, as the

casualty returns grew and grew until there was hardly

a family in the Island, grand or humble, that had not

lost a loved one.

Document. Le Poidevin’s Account

“The enemy were now coming across and surrendering

in larger numbers. They were badly wounded most of them

and had the very fear of hell depicted on their faces.

The surprise had been a success and had caught Fritz

quite unprepared. We were now on the move towards our

objective and covered many miles of ground, the Tanks

were ahead and we passed many dug-outs & huts where

Fritz had made himself snug since Aug. 1914. We met

with little resistance apart from snipers who were very

active from Nine Wood. My left section put 2 snipers

out of mess.

Although they had put their hands up and were “Kamerads”.

But they shot some of

my platoon. After some stiff fighting we took our Objective,

Nines Wood and made

use of the shell holes for consolidating our position.

I had the luck of capturing 5 Huns here, who gave us

some valuable information.”

Sgt. W.J. Le Poidevin RGLI

Document. Le Poidevin’s Account

“At one time 3 of us were surrounded with Germans.

We gave a good account of

ourselves till I got the effects of a bomb and was wounded

in the leg and thighs. I managed to crawl to a farmhouse

and applied first aid to my leg. After that I was done

and could not move. It was very fortunate that I was

found by one of our men & help secured to take me

back to the dressing station. It was decided to evacuate

Messinières. The RFA volunteered to come from

Marcoing & take away the wounded in Messinières.

While I was being carried along the Canal Bank my stretcher

was heavily shelled, and one shell dropped just behind

the stretcher killing two and wounding a third. I was

Providentially preserved as apart from being thrown

out I was unhurt. I managed to crawl about a 100yards

and stumbled across the Headquarters of the Inniskilling

Fus.”

Sgt. W.J. Le Poidevin RGLI

Document Chapman’s Account

Extract from a letter to Lt. Hutchinson from Lt. E.A.

Chapman.

“I feel I must write & tell you what a fine

company you had & what fine men they were. The NCOs

& men were bricks every one of them & as brave

as lions. They really did excellent work & by jove

they had something to put up with…….. They

all stuck to me like good ‘uns. Of course I was

at a great disadvantage not knowing the men, but in

the short time I had them I got to love them……

Never have I seen such pluck & endurance in any

men. The way they went over the top & went over

3 miles to their objective when they were fagged out

was a marvel & they dug in & reconsolidated

like good ‘uns & didn’t care a rap for

Shells or bullets or Huns……They were good

in rest, & when we went into the line again, &

got heavily shelled they showed utter contempt to the

danger.

They had some very unpleasant & risky jobs &

worked so well. The officers too were great. Poor L..?

was killed as you know in our first counter attack.

He was such a good chap. “Bottles” &

Morgan did excellent work. Poor Morgan has died of his

wounds.

“Bottles” I cannot get news of. He was exceptionally

good with his men & showed

himself a very fine officer. Plucky & full of grit

& he had some very ticklish jobs. I am sure you

would have been the proudest man in the Army if you

had seen your Officers & men at work.”

After Cambrai there was a real danger that the RGLI’s

service battalion would be disbanded and the men posted

to other regiments. There were no more Guernsey lads

to fill the ranks and after much pleading by the Lt.

Governor large numbers of English soldiers were drafted

to the Guernseys to fill the gaps left by the slaughter

at Les Rues Vertes. Most of them came from the 3rd Battalion

the North Staffordshire Regiment.

During the early part of 1918 the RGLI was in the line

at Passchendaele, perhaps the most unpleasant and unhealthy

part of the Western Front where the awful conditions

resulted in almost as many casualties as did German

shell fire. Meanwhile the Germans were able to move

huge numbers of troops from the Eastern Front to the

Western Front following the collapse of Imperial Russia

and were planning a final attack in the west with the

aim of winning the war, or at least forcing the Allies

to the conference table. The main weight of this attack

fell on the old battlefield of the Somme, but a subsidiary

attack took place in the Lys area of northern France.

The full weight of the attack fell on a Portuguese Division,

new to the line, which broke and ran. The 29th Division,

including the Guernsey troops, were rushed into the

line tostem the advance.

In the action which followed the vast majority of the

battalion became casualties. On 11th April Lt. Col.

T.L. de Havilland took into action 20 officers and 483

men. By 14th April he was reduced to just three officers

and 55 other ranks. But the German attack had run out

of steam and the last offensive was over. The battalion

had played its part in stemming the flow but at a terrible

cost.

steam and the last offensive was over. The battalion

had played its part in stemming the flow but at a terrible

cost.

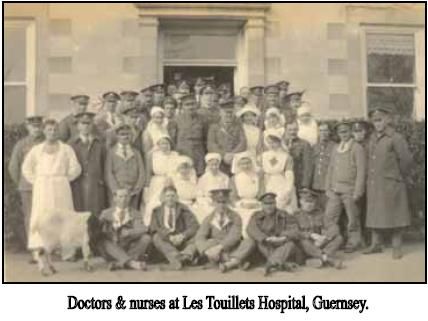

The wounded were sometimes

the lucky ones. “To cop a Blighty one” was

the dream of the men in the trenches. The reality could

be horrifyingly different. The most common injury sustained

in the trenches was a head wound from artillery shrapnel.

A steel helmet lessened the danger, but did not remove

it. Poison gas was most feared. Men died slowly and

painfully from its effects. Throughout the 1920s and

1930s ex-servicemen continued to die from the effects

of gassing in the war. Injuries inflicted to the mind

from unbelievable horrors seen and experienced, had

to be lived with. From the front line Casualty Clearing

Stations, the wounded were passed back to base hospitals

and in more serious cases, back to England - “Blighty”.

Some RGLI casualties were repatriated to Guernsey. They

were nursed by women and girls who very quickly had

demonstrated a toughness that belied their genteel backgrounds.

Nurses and doctors fought

death and disease without

antibiotics, penicillin, plastic surgery, skingrafts

or blood transfusions. All of these came later, as a

result of the research born of necessity during the

war.

Lt. Chapman’s Letter

No. 2 Red Cross Hospital

Public Schools Wards

A.P.O. 2 BEF Rouen

France

“ As you have probably heard I had my right leg

amputated as it was smashed by a shell & my left

leg is broken at the shin. It was the work of two separate

shells. Sgt. Le Poidevin came to my rescue & got

me down a cellar at the risk of his life & some

one else. I think it was my batman. I am pleased to

say I am doing well now & gaining strength every

day. My pulse & temperature are good & my appetite

is wonderful. I can eat anything, & drink anything,

& I feel remarkably fit now. I get rather bad nights

& lots of pain occasionally. The dressing of my

legs which takes place every two days is a painful procedure.

I am going to Blighty after Xmas.”

Lt. E.A.Chapman of the Buffs was in command of B Coy

during Cambrai.

The Survivors

After Lys a few men who had been separated during the

battle straggled back to the battalion but there was

no question that the RGLI would be able to go back into

the line in the foreseeable future.

A few days later the battalion was ordered to leave

29th Division and report to Ecuires where they took

over as guard troops on Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s

headquarters at Montreuil. There they licked their wounds

and received a number of drafts of new soldiers from

the depot in Guernsey. But the RGLI’s war was

over. In May 1919 the battalion returned to Guernsey

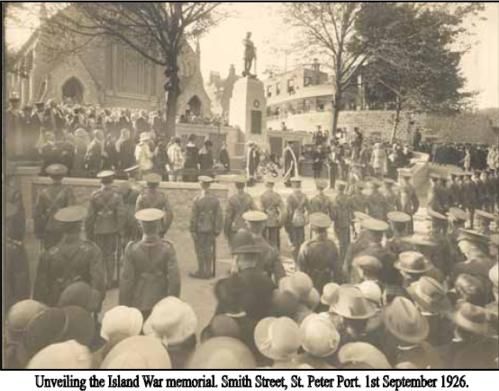

The Cost.

The RGLI left behind them in France 327 graves bearing

their cap badge. Many many more Guernseymen suffered

grievous wounds of body and mind while yet others had

suffered years of captivity in Germany. The war had

been won, but at a terrible cost which was felt in every

home in the Island. When the call for men came in 1939

the States remembered 1917 and 1918 and refused to send

the Militia to war.

The Total Number of men who served in the RGLI was

3549 Of those the number recruited in Guernsey was 2430

The remainder were transferred from England.

Of the 3549 men of the RGLI, 2280 served in France with

the 1st (Service) Battalion.

The following casualties were sustained.

Killed in Action or Missing, presumed dead. 230 - Died

of Wounds 67

Died of Sickness 30 - Total 327

Wounded 667- Prisoners of War 255

The following honours were awarded to the RGLI

Officers 1 Companion of the Order of St. Michael &

St. George

4 Military Crosses - 1 Member of the Royal Victorian

Order

Men 3 Distinguished Conduct Medals - 7 Military Medals

1 Medaille Militaire - 1 Croix de Guerre

2 Officers and 2 men were mentioned in Dispatches.

Here dead we lie because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

A.E. Housman 1859-1936

Men Killed in World War One

Note that this is an incomplete list

CHARLES JOHN BARNES - Corporal 3156

6th Bn., Royal Irish Regiment who died on Saturday,

9th September 1916. Age 28.

Son of William H. and Martha R. Barnes, of 3 Manor Cottages,

Colborne Rd., Guernsey.

THIEPVAL MEMORIAL, Somme, France Pier and Face 3 A

JAMES BATISTE - Private 3456

"D" Coy. 6th Bn., Royal Irish Regiment who

died on Sunday, 3rd September 1916. Age 31.

Son of James and Amelia Batiste, of Les Marais, Vale,

Guernsey; husband of Olive Blanche Batiste, of 2, Orangeville,

Bouet, Guernsey.

THIEPVAL MEMORIAL, Somme, France Pier and Face 3 A

C De G BLONDEL - Corporal 773

1st Bn., Royal Guernsey Light Inf who died on Monday,

9th December 1918.

BERLIN SOUTH-WESTERN CEMETERY, Brandenburg, Germany

II. D. 8.

GEORGE WILSON - Lance Corporal 2324

2nd Bn., Royal Guernsey Light Inf who died on Thursday,

7th November 1918. Age 43.

Son of John and Jane Wilson; husband of Christiana Wilson.

Born at Bingley, Yorks.

FORT GEORGE MILITARY CEMETERY, Channel Islands, United

Kingdom G. 223

Fort George is a fortress on the east coast of Guernsey

in the southern vicinity of St. Peter Port.

|